I finished a book a little while ago entitled A Reader’s Manifesto: An Attack on the Growing Pretentiousness in American Literary Prose and I loved it. I loved it so much that I’ve started calling it my little black book. It’s a long form literary critique using examples from numerous books, both-what the author calls-good and bad. It’s not a dry academic stuffy read. It is a fast, concise to the point essay about a specific topic that is not a high-minded far away abstract topic, but about book reviews, reviews people readers rely on to tell them what is good. If you love books, like books, or are thinking about reading more, I highly recommend this.

If you are thinking about writing about video games, I highly recommend this. In fact I’d call it damn near required reading, despite it being about another medium. Like Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, you need to read this. There are two main reasons for this. The first is that even though it’s about books, the critical writing he takes to task and the subject matter of such writing is equally analogous to the mainstream review writing and culture that revolves around video games. The second is the correct usage of the word “pretentiousness” with regards to it’s meaning in relation to critical analysis of the arts.

The second point can be made faster so I’ll deal with it first, before moving on to the bulk of the argument in favor of this book. ‘Pretentiousness’ is a word that gets thrown around a lot with regards to anyone who should dare to think above “duuuhh duhhh, explosions are fun.” Of course for most the word pretentious is far to big, so the meaning is implied or long explanations utilizing short words that could be summed up with ‘pretentious’ are used instead. You’ve seen them used. Recently it has become a hallmark phrase of people who want to avoid thinking about something negative or difficult.

It’s just a game.

What they are saying in effect it, ‘stop being a pretentious douchebag.’ The last word is added to connote the spirit in which the comment is given. That is what they are saying, what they really mean is, ‘stop bringing this shit up, I don’t want to hear/think about it.’

Pretentious – adj- 1. making usually unjustified or excessive claims (as of value of standing) 2. expressive of affected, unwarranted or exaggerated importance, worth or stature (Merriam-Webster)

That is what the word actually means. I want to establish that for most of the words usage or implied usage it doesn’t fit. I direct you to Moff’s Law for a full explanation.

So, if the word’s usage is not proper with regards to thinking critically about video games or any creative endeavor, then why would I apply it to the writing about video games after I just discounted its use? Because it is wrong to use it as a pejorative or first response against a thoughtful argument because it happens to be about video games, or again any creative endeavor. Even if you don’t agree with the argument or the argument is really outlandish and seemingly far fetched the term still isn’t applicable based solely on those grounds. No, pretentious is an adjective describing a very particular instance of critical assessment. It comes in two forms and this is where I segue neatly into the first point above.

A pretentious analysis is one that is unsupported or pulled from one’s ass. The first is self-explanatory. If you make a declaration or assessment and then do not back it up or explain yourself you are being pretentious. Saying the sky is blue and then not explaining that’s the color our eyes are interpreting based off of light refraction is not pretentious, it’s a shortcut. We know the sky is blue; it is a basic, natural, observable fact. I am specifically talking about statements of assessment or declaration of quality.

Over and over, B.R. Myers will excerpt passages, or rather sentences from books that were first excerpted by praising book reviewers. He only uses excerpts that were praised for their quality by high profile book reviewers first. In nearly every case the reviewer will describe the passage as great or insightful or maybe compare it to a literary great of the past and then give the quote. And then would move on. They would not defend their thesis that this excerpt warrants merit or mention. Meyers would often counter with a quality quote from a much better book. To show you what I mean I’ll pull one of the “so-called great literary passages” at random.

There’s something about German names…I don’t know what it is exactly. It’s just there. (White Noise).

Thank you for wasting my time then with those two sentences. I wont bother to give Myers appraisal of it, because I had to read this book and have been waiting 3 years to eviscerate it somewhere. I hate White Noise and in my Contemporary Fiction class I couldn’t help but feel, deep down, that it was bullshit. You can usually tell something about a book by its first sentence.

The station wagons arrived at noon, a long shining line that coursed through the west campus. (White Noise)

Yeah that’s memorable. I had to look that fucker up. Here are some other first lines:

“Call me Ishmael”

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…”

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

“It was a bright, cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.”

“Samuel Spade’s jaw was long and bony, his chin a jutting v under the more flexible v of his mouth.”

“In the week before their departure to Arrakis, when all the final scurrying about had reached a nearly unbearable frenzy, an old crone came to visit the mother of the boy, Paul.”

“The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.”

I shouldn’t have to label any of those quotes for you to recognize them or at least know where they came from. Every single one of them immediately holds your interest to read the next sentence. They are evocative and can be pulled apart word by word to discover the care and craft that went into them. The first line is probably the most important single line of any book.

There is nothing technically wrong with the first line in White Noise, but then there is nothing technically wrong with a lot of published books, but I wouldn’t call them literary genius. There is nothing technically wrong with the first line of The DaVinci Code:

Renowned curator Jacques Saunière staggered through the vaulted archway of the museum’s Grand Gallery.

Again, nothing wrong with the line itself, it even tantalizes with a few intriguing questions of “who is Jacques Sauniere?” “Why is he ‘renowned?’” “Why is he staggering?” and “Where is the Grand Gallery that it must be capitalized?” The thing is, now that I look at it, this is a better first sentence than White Noise has. It is well crafted, it may not be superiorly crafted like the above list, but it gets the job done and throws in a few mysteries. But the real bug I have with White Noise is the third and fourth sentences. After two short ones, we get a sentence that is half a page long. That by itself is not the problem. I love Proust and he holds several of the top places for longest grammatically correct English sentence in publication. (These go on for several hundred words. I believe the longest is in excess of 950.) I’ll reproduce Don DeLillo’s third and fourth sentences here; you can skim it instead of reading it.

The roofs of the station wagons were loaded down with carefully secured suitcases full of light and heavy clothing; with pillows, quilts; with rolled-up rugs and sleeping backs, with bicycles, skies, rucksacks, English and Western saddles, inflated rafts. As cars slowed to a crawl and stopped, students sprang out and raced to the rear doors to begin removing the objects inside; the stereo sets, radios, personal computers; small refrigerators and hairdryers and styling irons, the tennis rackets, soccer balls, hockey ad lacrosse sticks, bows and arrows; the controlled substances, the birth control pills and devices; the junk food still in shopping bags-onion -and-garlic chips, nacho thins, peanut crème patties, Waffelos and Kabooms, fruit chews and toffee popcorn, the Dum-Dum pops, the Mystic mints. (White Noise)

Yes, it is an enormous list and is important enough to take up one fourth of the book’s first chapter. The first chapter is two pages long. My teacher spent so much time explaining the meaning behind this list and the emotions its post-modern affectations and styling are instilling in the reader about consumerism. I did what Myers explains all people do, skimmed it. Unless it’s a shopping list for what we are shopping for and have to locate each individual item, we don’t take in a list. We skim it and confirm that yes it is a list. This quote was found in nearly every favorable review of White Noise a book I called later, because I would have failed the class had I spoken up at the time, a hulking waste of my time and why I couldn’t be bothered to read much of the material for that class. Part of A Reader’s Manifesto‘s well, manifesto is that much of contemporary literary fiction is meant to be skimmed and thought profound, but if one puts an inkling of thought or actually reads the words slowly, it all falls apart. The above is a perfect example. The effect only comes over the reader when skimmed. Should you actually read it, like we did in class and go down the list you can’t help but think it a waste of time. And then to be told it is a sublime commentary on consumerism, that’s pretentious bullshit. See, it wasn’t the writing itself, although when you add in the author’s aspirations and inflated opinion of himself, then it becomes pretentious, but it was my teacher’s assessment of it. For this is the second type of pretentious analysis, pulling it out of one’s own ass, or to be less colloquial – making an assertion and then supporting it with something that isn’t there. Also known as lying.

Back to that original quote that started this train of examples, what was it again?

There’s something about German names…I don’t know what it is exactly. It’s just there. (White Noise).

Ah, thank you. Again, what was the point of this line? You say there is something about German names, but don’t know what. In other words you could have not written it. No, it’s not “just there” you have to explain it. Don’t expect me to do the work. I didn’t bring it up.

All of these lines aren’t the problem. By themselves they are just stupid, inane and general wastes of time. The pretentious ones are the ones that try to inadequately defend them. They think there is a profundity to saying ‘I don’t know, it’s just there.’ Or as Myers puts it “I knew this without knowing why.” That is saying there aren’t the words to explain why something is, is some great insight. No it’s laziness. DeLillo has gone on the record saying: Writing is the concentrated form of thinking. This is like one of those Jon Stewart comparison moments where something great is compared to something stupid and contradictory that the exact person suggested for humorous appeal.

So, what does all that literary analysis have to do with video games? Quite a lot. The afflictions that infect the literary reviewers are analogous to the reviewers of video games. In condensed form, Myers suggests there are only three possible responses when a critic is asked to review a work of literature:

1. “Praise the novel and novelist.”

2. “Lament that novel is unworthy of novelist’s huge talent,” (But still praise it).

3. “Review someone else’s novel instead.”

To paraphrase:

1.Praise the video game with a high score

2.Lament it wasn’t as good as you hoped, but decent (And still give it an inflated high score)

3.Review another game instead

Number 3 isn’t as used, though given how much shovelware gets put out and not reviewed you can be sure that the mean, median and average review remains high.

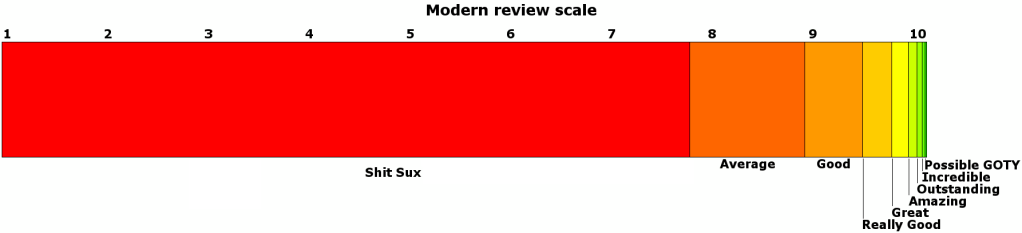

This graphic may be in jest, but is underlies a sad reality about video game reviews, the populous criticism. In some cases it may be about not having raised your standards enough, as it seems if it runs technically well then it guarantees a 6 already. But then this falls apart for the biggest of big releases, full of game stopping, save deleting, console crashing bugs getting 9s. Read that again, because they are not exaggerations. “Game stopping.” “Save deleting.” “Console crashing.” Of course I’m talking about Fallout: New Vegas. That the game got so many high scores despite not being able to run most of the time is unconscionable. As of writing this, the game has an 82 Metacritic average for the PS3 version, with the lowest score being a 60. The 360 version has an even higher rating with an 84. Yes, the developers fixed most, note only most, of the bugs through patches. A minority of consoles are connected to the internet meaning that most will never see those patches. These are the same people who buy only a few games a year. One of their $60 purchases is unplayable and it has an 84 average. I’m guessing this game falls under the second category of praise. It’s bad, but you still praise it because of its lineage/who it comes from.

If you want batshit writing and under supported or unsupported main stream video game writing, well you can go here to find an achieve of it.

It’s all about honesty. I’m not talking about reviewers supposedly being paid off to like or hate a game. Whether that happens or not has no bearing on what I’m talking about. I’m also not talking about badly written reviews in the form of poor structure or being unclear or convoluted at times.

This is not a well-written review. Back in January is caused a small furor on Reddit and later on the rest of the internet over people complaining how bad it is. The craftsmanship and tone have been criticized elsewhere; instead I want to look at what it says and not how it says it. It is not pretentious in the way I’ve described above. Greg Miller supports his claim about Dead Space 2. He says it’s a 9 out of 10, which on their scale means it is Amazing. He thinks it’s amazing and everything he says works to that effect and he supports it with evidence from the game. When talking about the game’s combat flow he gives the example:

Slowing down a Necromorph, blowing off its arm, and using the severed limb to impale the foe on a wall is a thing of beauty that doesn’t get old.

It’s a descriptive, specific moment. The line implies that it happens over and over, but the presentation of this example is so good the repetition doesn’t lose its horrific charm and is emblematic of the other moves you can pull off. It’s better than simply saying the combat doesn’t get old.

I know that “linear” is a bad word in the video game industry, but the package is so well done here that I can’t knock Dead Space 2 for taking me on a very specific ride that’s marked by awesome moments, environments that range from a cheery schoolhouse to pitch black rooms, and sound that’s so well done I’d find myself trying to figure out if it was a monster making its move or my dog rummaging in the living room.

This line goes on and would have been better as two or three sentences, but the point it makes is solid. He says the game is linear and though many do not like linear, the reviewer doesn’t care with regards to this particular title, because of the environments (which he gives examples to show their range and variety), picks out the sounds as integral part of the experience and of course the “awesome moments.” I’m not going to go too far in defending the review for reasons I linked above. It’s slapdash writing that for a site as major as IGN reeks of unprofessionalism. Poor grammar and tense changes plague the thing, but like the Dan Brown line it’s workman like. The review is not exemplar, but it does its job.

And then there is the other type of review, the kind of review that seems just to list a game’s qualities and assign a score. Author Jen from TheGameFanatics wrote such a review on Dragon Age 2. Forget even the writing quality, which is no more than banal, but that by the end of it I couldn’t tell if she like it or not or rather if she would recommend it or not.

The first half of the review is plot summary, but doesn’t say anything about it. She mentions she got a Final Fantasy XII vibe from the story, but what specifically gave her that vibe and is that a good or bad thing in her eyes. I don’t know. It says that making friends and gift giving is easier than before, but again is that good or bad. Then it goes on to talk about the features of the game like interface and combat, but it makes no pronouncements about them. It might as well be a features list, because that is what it is, a gussied up features list. When she does give her opinion it’s nearly always negative: confusing and laborious code inputs and installs, annoying popups, poor sound mixing, dated graphics, bunch of glitches and bugs (including a screenshot of one) and she notes two weeks later there still isn’t a patch. That’s quite a lot of complaints. She finally lists a few points she liked, for example the fact the game is never the same twice or that the game offers choice, but what does that mean? How does it make sure it’s the never the same game twice? Ok, it offers choice, but to what degree and how good are they?

Again, there is so little there I couldn’t tell if she would recommend it or not. If she did I figured it would be one of those decent above average, but not exceptional recommendations then I see it got 9 stars. What the hell? There is nothing in the text that warrants the final-word praise like it does.

It’s not the only one either. IGN’s Homefront review makes a lot of declarations like it’s not an elite shooter, or the shooting, voice acting and sound is serviceable, but nothing special. The thing about it, it never says why. I only have Colin Moriarty’s word for it that all of this is the case. He never backs up any of his claims with evidence from the game. At least Greg Miller did in a few spots.

Then we have Susie Lye’s Homefront review at GameNTrain that does what I thought we moved passed, splitting the review into looking at the individual sections (gameplay, story, graphics, sound) in turn. That doesn’t help me if I’m buying the whole product. How much does each of these matters when looked at as a whole? Is sound important like in Dead Space or Silent Hill? Do the graphics detract from the shooting or can I make out what I’m doing? And what exactly is “Gameplay Overall?”

Or Ken Laffrenier of XboxAddict who doesn’t get to the game in his review until it’s a fourth of the way done. Then he waxes lyrical in such a convincing way, that you know he likes the game, but it doesn’t tell you why you’d like the game. It describes little about the actual game and even less why any of that is good. It comes to a head in a really perplexing paragraph where he explains the story is amazing if you had read the companion novel, which expands on the invasion through the eyes of “an intricate character” that narrates in the game, but I don’t see how between level voiceover narration is a good video game story. Also, why is it good if I have to read a supplemental novel to get everything? This isn’t even a right to his opinion thing, it’s just wrong. The game’s story is good, because I read the book? It talks about influences and mentions some stuff that’s in the game, but never seems to say anything about the mechanics; you know the actual things you press buttons to do in the game and never gives qualifying statements. This isn’t just bad it’s baffling.

It comes down to being an honest reviewer. Not just honest with the audience, but honest with yourself. It means not calling a game average and then giving it a 7 or up. 7 out of 10 is not average, not even close. The mathematical average on a 10-point scale is 5. On a scale of 100 it’s 50. You have to be willing to use the full range of scores. The most common numbers you should be giving out if you are a review site is from 4-6. Most games should be in that range. Kill Screen says the range should be between 3-7, but the main point holds. If you are being honest you should recognize most games aren’t amazing or incredible or phenomenal or life altering or “the most important video game of our generation” or bad or terrible or dog piss. Most games are ho-hum, run of the mill, bland, forgettable, in other words: average.

Now with this shocking revelation washing over you, here’s another: reviews are opinions. Reviews are subjective. Subjective does not mean objective. The number attached to the review is not scientific, it is not an objective result derived from critical observation. It is a subjective opinion derived from critical observation. If a reviewer gives a substantially different score from another reviewer it does not mean one is wrong and the other isn’t (if they both supported their arguments). It means they disagree. They have the right to their own opinion, what I’m championing is the assertion that they do not have the right to their own facts. Regardless of anything else, how good the animation is, how deep the story is, how nuance the characters are, how tight the controls are, New Vegas is not a good video game because of the game breaking bugs and coding errors that will not allow it to run. I don’t care how good your game mechanics are if the game freezes up on me consistently and constantly. Your game is broken and is not good.

I will end this with a few reviews sites or in some cases sites that do reviews that are honest. I may not agree with some of them, hell some of the reviewers on the same site do not agree with one another, but they are honest for the reasons I have outlined above.

Game Critics is the most mainstream game review site here. They hit all the major releases and much of the minor ones and unheard of one as well. They use the full scale and are not afraid to exercise that against major release titles like Brad Galloway’s 2.5 for Dragon Age 2. If a reviewer disagrees strongly enough, they will do another full review as a second opinion, with a new score. I’ve seen third opinions too. Each review was given a different score and each one was a supported argument.

PopMatters is a site that concerns itself with all forms of popular culture. There is the Moving Pixels blog, which is higher minded and analytical criticism, but they also do reviews. Again, these use the full spectrum of the 10-point scale and are backed up arguments. Even if they flounder like their recent Dragon Age 2 review. With regards to support of her score, Kris Ligman defends it in the text. She liked the game despite the flaws it presented even if she is not entirely sure why but says so. She admits she may not be exactly sure why, but she says so and gives her best estimation. You may not agree with it, but that is the act of an honest reviewer on an honest site.

Yahtzee-love him or hate him-is an honest reviewer. In his very hasty, no pause video review he delivers his opinion in around 5 minutes every week. What is more interesting to note is how his reviews are often received. He is the only reviewer I mention in this post not to use a score and often his watchers are confused as to whether or not he likes a game. This is the viewers’ fault and not his. He is very clear whether or not he like a game, it’s just the gamer audience is so used to the extremes they cannot recognize gradients anymore. Some games he likes a little, some a lot and some not at all. He may not follow the mainstream, but he is always true to his own opinions and always backs them up.

Paste Magazine has a more limited video game section and does less frequent reviews, mostly on high profile releases. They have some of the best-written reviews out there and go beyond simply what the game is, how well it works and how much they like it. They try to explain the game’s appeal and the effect it has on a player. Kirk Hamilton’s Limbo review should be proof enough. It says little on the game itself, but after you read it you know whether or not you want to play it yourself to experience what it has to offer. To keep consistency Kirk Hamilton gave Dragon Age 2 a 4.5, to him a “forgettable.”

Kill Screen has the best spiel on game review scores I might have ever read. I referenced it above, but please read the whole thing here. Now they don’t do the volume that the major mainstream sites do, nor have they focused much on the AAA titles. Their editor-in-chief has said they are not averse to them; they just haven’t received those submissions yet. They’re focus is mostly on indies and the iOS/Android platforms. I’ve seen their scores go as low as the 20s and the highest I’ve seen to date is a 79 out of 100, which was later changed to a 93 and that was a nothing but praise review, also the only 80+ they’ve published. They have high standards and do not sacrifice them. They want to elevate video games and video game writing so they must hold themselves to a higher standard.

These are the honest sites with well-written reviews. There are plenty of examples of well-done reviews within each of them. Most reviews are subject to the hype. They are influenced by it and tainted by it for one reason or another. The thing is to remember, when the game is no longer new, when the game is years old and the hype has died down, the commercials are no longer on TV and the news/preview/news cycle has stopped, all that’s left are the words. All that’s left are what the critics had to say. I’ve gone back to some of the major sites to see what they had to say on modern classics like Shadow of the Colossus and have been sorely felt wanting by what I found.

You may have found it egregious that a lot of what I had to say focused on the scores a game was given. I did it because that is what the industry, all three sides of it are, are focused on. The developers/publishers makes many of their decisions based on what the critics score it, the average consumer makes his decision or validates it with the scores, and the journalists, as much as they rail against them put a lot of effort into defending them. The score is the thesis in a way and the text is the support for that thesis. If you think a game is a 9.0 then your writing has to support that, just as if you called a game a 1.0, the writing must support that. But most of all raise your expectations to reality. Set the record straight. A 6 or a 7 is still above average and could be that fun game. Save the high scores for something that truly deserves it. And when I mean high I don’t mean 9.0 and above. The inflated review scores are a major part of the problem; so major you could say they are the problem for they cause all the others. 7,8,9 and 10 are all high scores they are just different degrees of high. Arguing the score is pointless, it is his opinion and so long as he supports his opinion it is his. But as it goes, there is opinion and then there is just plain wrong. If the reviewer calls a game mediocre and grants it a 7 or an 8 then yes he is wrong.

You can argue that the 10 point method is not the best way to go and sing the praises of letter scoring or 5 stars, but it all comes down to the same thing: you must be honest and use the full range of what ever scoring method you use or your opinion has no value. Everything is not wonderful, just like everything is not crap. You have to explain yourself, because the explanation is the important part. Not the score and not the ‘your opinion.’ It’s why you have that opinion that matters, because if you tear the game apart the person reading may feel they want to try out the game, because what you didn’t like may appeal to them and vice-a-versa.

You really should pick up A Reader’s Manifesto, it’s a brilliant piece of literary criticism, but more than that it’s criticism about an embedded review culture staked in keeping itself afloat. Myers notes that in the period before he wrote and published it there were strong rise in sales of classic novels, because the reader of quality literature had been burned and knew they could no longer trust any sterling review, because they were all sterling. The writers gained an inflated image of themselves, where in Cormac McCarthy’s case he had produced some great craftsmanship, later seemed to be phoning it in because no one told him otherwise. You tell someone what they are doing is great and wonderful when it’s not, it will not drive them to do better things, constructive criticism will.

The title A Reader’s Manifesto is there to assert its literary origins about the review culture around books and more specifically post-modernism literature that is presently in vogue. But it is more than that. It can speak to any review culture, either as a warning or as a mirror. A Reader’s Manifesto is for review readers as a whole. The problems and arguments may be about books, but the defensiveness, ad hominem attacks and step-by-step analysis of the response to any challenge to embedded elite reflects on all of us.

Comments

Myers’ book is one of a long history of titles angry at the author’s exclusion from literary culture. The tone of the book is one clamouring for anti-establishment credibility by quoting darling authors of his day. His expansive attack on White Noise was famously the subject of most people’s problems with The Reader’s Manifesto. You and he may not have liked WN, but it was popular at the time because its dry tone and simplicity. You were certainly taught it poorly by the sounds of it. The novel is about class anxiety and doesn’t need a huge exposition of postmodernity to explain a damned thing about it. Literature classes are also easy to hate because they are culturally competitive spaces. When I taught postmodern literature I took a friend’s advice and did the first week on how not to be assholes to each other and be honest about the work we were reading rather than look for easy answers – and we read lots of awful prose to get warmed up. But if you’re going into WN looking for a preachy answer to why modern life is shit and why people are consumers, well you’ve set the stage for dumb, which is your teacher’s fault.

But I found Myers’ book to be incredibly coloured by his quite personal literary tastes. Pretentiousness can be read not just in unsupported prose but in prose that puts the author as cultural gatekeeper to some experience or another. To be welcoming and kind as a writer is incredibly hard – and you can see what happens when authors (say Murakami and Eggers) go down that path. Ie, you get accused of pretentiousness by bowing too heavily or not heavily enough to literary convention. But he advocates an incredibly boring and narrow view of literature. I would say its conservative. Are you allowed to be poetic at all? Nowhere in the book is there anything approaching a kind word about all the forms of inefficient writing that are massively fun and explain, in their baroque madness, things than sharp intense prose does not. Once we eliminate all of Myers’ enemies from the world, do we still have poetry of any kind? Or is that too pretentious as well?

Whenever I hear someone complaining about literary pretentiousness, I reach for my gun. There has been a culture of stark, powerfully simple writers pissed off with flowery prose for what – hundreds of years now? I’m happy to represent the embedded elite and provide any and all ad hominem attacks and defensiveness for the purposes of the prosecution. The literary elite hated Delilio at first and then he became the establishment. He wrote in a popular style with popular ideas that everybody seemed to get along with. Contemporary literature – like contemporary anything – isn’t just about time but about being part of the ongoing conversation. If Myers’ point was “White Noise was really popular, and critics liked it and quoted passages from the book that don’t make much sense”, you sort of have to say, welcome to the fucking Thunderdome, dude. Didn’t he also assert that the characters in WN exist just to express Delilio’s thoughts rather than act as fully fleshed out people? God forbid. He can have his muscular Woolf and Melville and Beckett.

The thing that was the most odious about the book was the squealing defensiveness he took up when people responded to the original essay and he made that… half the book? You can’t criticise him because that makes you a defender of the elitist consensus reality of literary culture? How’s this for short and sharp – ‘The lady doth protest too much.’

If this comment sounds negative, its not. I actually agree with your conclusions for game reviewing 100%. There needs to be a full on cultural shooting war within games to eliminate and shame bad game reviewers into assisted suicides if at all possible. They are the weakest link. I used to review and have the most telling bits of writing cut by editors because they were too negative – so I’m always looking for the context of reviews and I will often just stick with the reviewers I know and trust, and go out of my way to follow them as taste-makers. I can no longer just go ahead and trust a review of a random game. Perhaps this is sad but I am liberated by not looking to reviews for consumer advice and instead looking for taste advice.

I was worried for a second that you would focus wholly on the literary section of the post, which I used to highlight the issue as presented in A Reader’s Manifesto and then compare it to the issue of video game reviews. You seem to take some consternation with how I may have been presented the material. I was given the book list and told to have this much of the book finished by this class and finished by the class after that ready for discussion on what we read. My teacher set up nothing of how I would go into the book, we read it and then would discuss it. It’s what I got out of it I have the problem with.

The amount of time we spent on those first two pages and that passage I quoted was disproportional to the rest of the book. Hence, why it stuck out in my mind. It didn’t strike me until afterwords as I thought about the book more I didn’t like it. There was no story I could grab hold of, no character I could latch onto, and things happened for no reason and were never explained or even touched on again. You could say that’s the point, that our world is not understandable, but that’s a cop out. We hold our stories up to a much higher degree than real life. Our stories must make sense where real life is allowed to confuse us. If you want a work expounding on the in-understandable qualities of life, then do it with your content, not your delivery. I didn’t hate all my literature classes, or even that one other than it being too damn early in the morning.

I didn’t like the book. Nothing appealed or spoke to me. For the most part Myers echoes my thoughts in a much better written way. DeLillo wrote a better book, not great but better. It’s called Mao II.

As for the pretentiousness, I think it’s telling that his article was attacked by the reviewers and not the author’s he criticized. As for the second half of his book, so he’s not allowed to respond and criticize the criticism that was launched at him? That particular kind of back and forth has a name it’s called debate and I’m often confused when people say you can’ criticize criticism. Plus, it was mostly ad hominem attacks that had little to nothing to do with what was said. The pretentiousness came from the reviewers with their dogged insistence they were right in the face of very bad prose. A bad writer can be a bad writer and I will never call it pretentious, only bad writing. I call pretentious at the insistence of quality based on nothing, but the “because I say so argument” is pretentious. By that degree Myers was not pretentious, he very much explains his position, but the reviewers he criticizes do not in their reviews, nor in their response to him.

As for flowery prose, I’ve got no problem with it. It’s when it turns purple or just batshit I take issue with it. Twilight is full of of flowery prose, but it’s awful. Dune is full of it too and it’s much better. Shakespeare is full of it and it’s beautiful. I don’t want to echo his points, but he doesn’t rail against flowery prose so much as he rails against nonsensical or contradictory flowery prose. His personal preferences of course will color his writing, he is a human being, but that doesn’t make his points invalid.

The short of it is, if I were to take the same critical eye I explained and demonstrated in my post above to Myers and his detractors I have to say Myers isn’t the pretentious one nor the “squealing defensiveness” one. You could have argued his points on specifics and it would indeed be a difference in taste, but they didn’t.

Assisted suicides, I’m sorry is way out there. I don’t advocate violence against human beings, especially for bad writing. I’m not the greatest myself. The myriad of factors and issues behind video game reviews are vast. I could only focus on the resultant output. There may be good reviewers out there where there output looks like shit for the reason you example. But we criticize what we got, not what we wish.

I’m glad for books like his that try to raise the stakes and try to keep literature honest, I really am. But it lacked impact for me at the time and came off as low-hanging fruit. I loved the debates at the time. I assume you were being dry in describing to me what a debate was, and actually I give him credit for fully responding to everybody who had a problem with the essay. But I don’t actually don’t think its telling that authors didn’t respond. They hardly every do. And I saw two ad hominem attacks at the time that called him, I think “stupid” and “out of touch”, both of which were unfair characterisations of him. But there was also a sustained, thorough rebuttal by several people. Now if you’ve read the whole debate and see no defensiveness on his behalf, and thought White Noise was ambiguous garbage, then you and I see writing very differently. My problem with him was very specific at the time; that it was his way or the highway – and that all of literary culture must be in some consensus hallucination. Anyway, enough about obscure literary arguments.

I actually thought your connection of Myers to game reviewing was spot on. Game reviewing often lacks the basic writerly qualities that form the absolutely bare minimum. I’m interested to know how you see a writer like Tim Rogers fit into your schema. His 2006 80,000-word review of four games for Insert Credit is full of lengthy stories about his sex life and being a hipster doofus living in Japan. If there’s a game writer who can be accused of breaking the rules Myers lays out, its him. But very many argue its good writing.

I would just like to state for the record that, despite that chart, we hate everyone equally 🙂

thanks for mentioning us in your piece

I give this post a 94 out of 100, because the only issues I could find with it (grammatical errors and typos) will most likely be fixed with a patch at a later date. 😉

Seriously though, great job Eric. I will make certain that any of my future reviews will be Manifesto compliant.

Christian: “There needs to be a full on cultural shooting war within games to eliminate and shame bad game reviewers into assisted suicides if at all possible.” This had me in stitches.

@Christian Tim Rogers is an interesting example to say the least. I never read that particular review, but I use to read him, or rather try to get through him when he wrote a regular column for Kotaku. I’d liken him to Hunter s. Thompson in his style and structure. I think he was just too long winded, even for long windedness. There is nothing really wrong with it other than it was on the internet which is diametrically opposed to such a type of writing, especially in such large quantities. The essays of David Foster Wallace are somewhat similar, but because they are on paper I find them a breeze to read through. Hope that clears that up.

@Niero Thanks for stopping by, have no clue how you found it unless you search for that graph every week or so. I have no idea about your sites reviews in particular other than the 10 out of 10 you gave Deadly Premonition. So at least you don’t hate everyone equally.

@nordicninja I saw your comment after I woke up. It came in while I was in the middle of issuing said patch. Finished two hours later. I caught everything I could and made some of the language clearer in places. As for Manifesto compliant…

I think I need to say to all readers who come and read this afterwords. I will not be stalking review sites or hunting anyone down for anything. I am not an enforcer, just a disappointed writer.

Arstechnica.com has my favorite review system and style out of all the websites that I’ve seen produce/post video game reviews. They waste no words getting straight into the nature of a game’s mechanics and describing the experience of playing the game. Ars writers usually say more in their reviews than an IGN or Gamespot review that is two or three times as long. They sum up the review without arbitrary numbers or stars and rate it either buy, rent, or skip. Which is all most people really want to know.

They recognize what the important parts of a review are and serve those essentials skillfully and succinctly. The distinction between a review and critique is lost on many game reviewers, leading to their hodgepodges of superfluous and vague writing and my constant cravings for substance. I hope Arstechnica never goes the way of the Escapist and caves in to numeric scores and the maleficent hydra that is Metacritic.

The more I think about it, the less I like the distinction between reviews and critique. What I read to learn more about my new laptop were reviews, what I read to choose which refrigerator I’m going to buy are reviews, what I read to learn about any creative endeavor is a critique. Game reviews, movie reviews, book reviews are all critiques on the bottom rung of criticism focused on the question of ‘is it worth your time and money?’ I hesitate to say good, because it’s more about is it worthy. Something bad could still be worthy of your time if it’s unique and cheep enough or if it’s one of those so bad it’s good titles. Many game reviews, especially those that analyze a game aspect by aspect are trying to be reviews and to me that is a huge step backwards. That is the laziest type of organization possible and doesn’t help me in the slightest. I could understand splitting up the single player and mulitplayer, because they are fundamentally two different games using the same art assets, but sound and graphics, what does splitting those two up tell me?

I haven’t read Ars Technica reviews, since they don’t use scores I figure the vast majority of gamers don’t either. For some reason if it doesn’t have a score it isn’t a legitimate review so runs the logic in their heads. I’ll take your word that they are well written and on topic.

Another interesting point that a friend brought to my attentions is how he reads reviews. He likes Game Trailers and I couldn’t understand why, especially after he told me what they were like. They weren’t reviews so much as bullet points of features. He doesn’t want an opinion, he wants to know whats in the game and he’ll decide for himself. Then I asked why not go to wikipedia, to which he responded he would, but he’s already on Game Trailers watching videos so it’s easier to watch their reviews or overviews. Overview is what they are and a much better term. The thing is I’ve never seen him complain, really complain about anything he’s played so I’m not entire sure what his measure of anything is. I think it might be, if it runs I’m fine with it, which seems to be what most reviewers judge by whether they do reviews or “overviews” and that doesn’t work for the majority of people.

I’d go further and suggest that review scores should be calibrated around a 20 or so as the average game and then work from there. In general a significantly below average game isn’t going to be widely played. Quantifying exactly how poor a game is while sometimes entertaining isn’t particularly useful in determining if I would enjoy the game. Its unlikely I’ll enjoy a 10 or a 20, except in some so bad its good kind of way, even though the 20 is better then the 10.

However it can be useful to have greater precision when quantifying how good a game is, to distinguish between for example an outstanding game and a game that outstanding except for a couple small details but still deserves recognition for being outstanding. Based on this it seems that a scoring system that marks 20 as an average game and then scales linearly up to 100 would be the best system.

I heartily applaud your critique of the unbalanced use of scale in video game review scores. In my view, much of the confusion comes from using a linear scale to represent a variable — quality — which is best represented by a bell curve.

Several years ago I proposed a dual metric based on the theories of Ludology and Narratology. My implementation used scores for each metric ranging from 3 to 18, like ability scores in dungeons and dragons. I was ridiculed by Penny Arcade 🙂

Anyway, if interested you can read about it here:

@Jon I thank you for your applause, but I don’t agree with your own methodology. The dual metric is an interesting idea, one I’ve heard before, but your execution is regressive. I read your post and the 3-18 scale is a novel way to alter the scores into the proper displaced bell curve it has to marks against it.

One, this is a scoring system target directly to geeks, it alienates the mainstream from understanding at a glance what it is. They see a 10 and they will think ‘great, this game must be amazing’ when really it’s slightly below average. Even among geeks and video game enthusiasts, it speaks to a small segment that knows about DnD ability generation and more-so has to understand the finer points of the math.

Second, it doesn’t alleviate the problems of disproportionate scoring. What is to stop a site from sliding results of the scoring up. Just because there is math behind the system doesn’t mean people will follow it. The 1-10 scoring system has math behind what is average and it is blatantly disregarded. The change in scoring methodology changes nothing and puts a new suit on the same problem.

On your dual scoring system however, it’s a nice idea, but again it’s your execution. You divide the scores into narrative elements and ludic elements. this is a big enough problem in critical circles that we don’t need reviewers throwing their support behind arcane thinking. You are doing the same thing as the reviewers above by assign a different score to a different elements of the product. Graphics, sounds, story, gameplay etc. Many mainstream sites are abandoning this way of criticizing games. You do address there are two fundamental parts to a game and its rating both these parts under the same heading that is a big cause why scores skew to one side of the scale. Games that work functionally as a piece of programing and nothing else tend to get 6s at minimum. Yes that the program should assemble its algorithms correctly is important, but games are also artistic expression and we are so far beyond ‘if it works it’s good model of programing.’ Even word processors have to do more than function to get good reviews. If your dual scoring system was instead ‘artistic merit’ on one side and ‘does it function’ on the other I might agree. It would also clear up Fallout: New Vegas, which by many accounts has brilliant artistic aspirations, but it still fails under the crushing amount of functional bugs. Then I could accept it getting a 9 if it was offset by a very visible 1 explaining it doesn’t work half the time.

Thanks for the comments Eric. You are of course correct in pointing out that using a system with a better-suited distribution doesn’t actually solve the problem of skewed review scores. I do think that a break from tradition is helpful however, since we’ve all been conditioned to think of a 6/10 as bad. A scale with a concrete distribution is best since it has well-defined average. Linear scales leave too much to interpretation. Although you are right that even good scales can be used incorrectly, I believe we should still choose the best scale for the job.

Sometimes I regret using the L/N terminology, since it carries so much baggage in the field. Artistic merit is a good substitute for Narratology, but I wouldn’t want to reduce Ludology to mere programming competence. Ludology can encompass that if it impacts the game design and playing experience, but Ludology consists of much more.

Since you connected this article to Meyers, it’s kind of hard to separate him from it but I highly recommend you go out and read those books he derided; you read White Noise, yes, but have you read it recently? Personally, I’m not a fan of DeLillo, but not liking something doesn’t mean you have to despise it or not see how others might.

Another big mistake that I see readers make (and I do not accuse you of doing this, but I’m talking more in general) is that when they read something like Pynchon or DeLillo, they read it for plot or try to look up every single word and reference as they go along. That’s incredibly distracting, and forgets that most novels should be read for impact–for feeling–and shatters the effect of constant reading. Just save the word-hunting for your reread or after you’re finished a section of the novel; in general, I would discourage treating a novel like a puzzle.

I’d also recommend you read up about Meyers, or check out his reviews and articles at The Atlantic; as you will find, he invests some very bad politics into everything he writes, and surprise-surprise, he always dislikes the prose of something that does not fit his world view. (Did he lobby the “anti-American” label at DeLlilo in A Reader’s Manifesto? He certainly does it elsewhere.)

Another big problem is how he values plot, plot, plot over “empty characterizing and philosophy” then holds up Faulkner, Melville, etc. as good examples of plot. Beyond that, everyone knows plot is literally the most mundane thing about a novel. E.M. Forster, in his 1927 Aspects of the Novel (another book you might find interesting, as it certainly has some interesting relations to games), splits it into two aspects, “story” and “plot.” The descriptors are not what you would think, and probably the reverse of what we would label them today: Forster weighs “story” as the most basic of a novel’s aspects, comparing it to the “tape-worm,” curling out of its host. A boring person asks “what will happen next?” he tells us, and that is never more relevant than in our Spark Notes society where people endlessly debate plot “holes,” plot mechanics, what I would do in my version. This is a society that considers talking about plots in video games as a good weight of their worth as art, and claims substance is separate from style (in the visual arts especially, substance=style).

Needless to say, Meyers sort of Internet forum thinking is not just wrong-headed, but extremely dangerous both to criticism and Literature itself. It’s good to see you got something out of Meyers that is useful for game criticism, but I cannot condone someone who actually hurts a culture that is already near visual and prosaic illiteracy.

@Andrew_Lavigne This is going to be difficult to respond to as you go to quite a few places, so bear with me.

I read White Noise about 3 or 4 years ago now. I did not like it. I couldn’t follow it’s plot (aahhh, I know naughty word) or it’s meaning (obscured by it’s own insistence to it paradoxically), but also it’s point. I couldn’t figure out why I had read the last 250 some odd pages. I had learned nothing, gained nothing, matured nothing, been exposed to nothing in a book as far as I could tell was about nothing. I don’t despise it’s existence, I despise the acclaim this Literary nothing has garnered. I have not read his Magnem Opus Underworld and given it’s length unless my local library has it on disc I wont. But I have read Mao II, which I liked. It wasn’t spectacular, but I’d still put it on the positive end of the scale.

I’ll skip the plot discussion for now and just say I know only one person who ever word hunted through reading a book (this does not count looking up the occasional word as that can sometimes unlock the whole meaning of a passage or obscure it) and that was a specific case: James Joyce’s Ulysses. I did not realize this was a thing, nor would I propagate it. Though neither was Meyer. His word choice talk was for the authors, not the audience.

No he did not lob the label “anti-American” at anyone in this book. He may not have even used the word pompous, though it was implied several places. In fact his entire book was devoid of capital P politics. And frankly unless the work addresses, devolves or is about politics the author’s shouldn’t contaminate the work. Whatever happened to “the author is dead” (one of the most misunderstood essays in literary criticism) with regards to the text. Regardless of what he says elsewhere, it’s what he says here that matters. As for disliking the prose that does not fit his world view, that’s all of us to one degree or another. He is a man with the right to his opinion. It doesn’t matter.

Now we get to have our plot discussion. Is plot the most important thing in a novel. Not necessarily, but I’d say in 8 times out of 10 (number pulled out of my ass) it is. Plot isn’t the end all be all of a story, but it is kind of important. Even trip fests like Mulholland Drive or The Crying of Lot 49 have plot. Plot is the structure upon which everything else is built in the reader’s mind. The creator might have characters or themes or just an image he wants to convey, but in the actual conveyance it has to be around plot. Walls and ceilings cannot stand without foundations and supports. I agree our culture is too focused on plot, because that is as far as our education goes as a culture. The NYT bestsellers list are full of books that are “page turners” built on “seeing what happens next” but good books too have a plot. But the debate about plot holes and plot mechanics is kind of important, because there is some problems if your book cannot stand up to that scrutiny. I don’t know what Foster calls story or plot, but I will put that book on the pile. I have my own theorizing about how “story” “plot” and a third term “narrative” all coalesce together with their different meanings. It may or may not see the light of day depending on how interesting it ultimately is.

Yeah, the plot of video games are nothing to write home about. Especially when their meaning is only tangentially related to them. People who hold them up have never been exposed to anything better or anything thought provoking before.

I know little about visual art criticism, so I showed a friend who studied it your comment. He rolled his eyes. Mentioned Rococo and handed me a book. From what I understood of his abbreviated explanation, “substance=style” is not true. Correlation does not mean causation. Innovative and interesting style in the visual arts tends to go along with thought, not always and that’s when you get empty prettiness. This is where the baroque movement came up. I’m late to this, but I figured it’s about time I get some visual arts learning into me if I’m going to continue with video games.

I’m not sure what part of my paraphrasing of Meyers’ book is “Internet forum thinking” so I’m going to assume you meant his other writings. It’s ironic, because the second part of his book is an extended response to the many criticism/attacks/and Internet forum like behavior he had to deal with from the literary community in their attempts to discredit him. Though given the caliber of pedigree this mudslinging came from I can only wish all Internet forum trolling went like that. (Also, I’m assuming you meant Meyers and not me when saying a person “hurts a culture that is already near visual and prosaic illiteracy.” It’s just that books aren’t a visual medium and video games are that I’m confused.)