Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days is a Victorian era adventure novel following the exploits of Phileas Fogg and his valet Jean Passepartout in their attempt to win a wager. Done as a series of episodic exploits that take place in various countries along the route, it’s easy how one could adapt the book’s structure into a video game. However, a novel written in the 1870s is not something that will work as a video game in the 2010s. Not the least of which is the book’s very imperialistic vibe. At the time the British Empire encompassed approximately a quarter of the globe, such a vibe was unavoidable. Fogg himself, while positively magnanimous for the time, comes off more than a little bit of a condescending dick nowadays. While the original text will always exist as it does, any adaptation has certain obligations to the time it exists in.

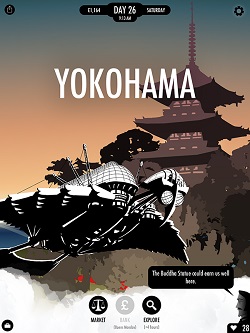

Coincidentally, when inkle Studio’s 80 Days was released, I had just finished rereading Around the World in Eighty Days. I hadn’t read the book since middle school and had forgotten quite a lot of the story’s particulars. Given the fortuitous circumstances what else could I do on my inaugural attempt to circumnavigate the world than try and duplicate Philieas Fogg’s path from the novel.

Right off the bat I think I can say many more interesting things happened to me during my travels than did to Fogg and Passepartout in the book. The novel is more interested in the act of traveling than in the places the men are traveling to. Case in point, the book sort of skips them to Suez saying nothing of importance or worth mentioning happened while crossing the entire continent of Europe. The same cannot be said of the player. I was hijacked by a female airship pirate and dropped off near Turkey to deliver a package before being accosted by a man being chased by police. It’s only once in Egypt does the novel pick up with the main conflict of Detective Inspector Fix. When I arrived at Suez, Fix was indeed there at the customs office. I, as Passepartout, spoke a few words with him, mentioned our journey around the world and was wished well. Fix did not deign to follow. There is no bank robber in 80 Days to necessitate Fix get involved. He is just another individual in this world, a wink and a nod to the original work.

80 Days has the mcguffin of a challenge of making the trip in 80 days to give the whole endeavor purpose and a deadline for the player to meet, but in the end, unlike the book, the real purpose of the game is to explore the world. Fix was a nod to the original novel, but also a recognition that he was not necessary in this version. The conflict here is generated from our own ability as the player to navigate the trip. Circumstance is our antagonist, not a determined police officer.

Not a lot happens on the steamship to Bombay in the novel. The book mentions Fogg bribing the captain to push the boilers a bit, so they arrive a few days ahead of schedule, and Passepartout chats with Inspector Fix, but the time crossing the Indian Ocean is largely empty story space.

Something that has to be understood about the era in which both the book and the game takes place is that careful timekeeping was a very new thing. Prior to proliferation of the railroad, time was an abstract concept, one where generalities ruled. Clocks would vary from town to town, village to village, if they had them at all. Standardized time keeping was unheard of prior to the presence of trains. Trains revolutionized the world, both in travel and trade, but also in how people thought about the world. Suddenly, people needed to know exactly what time it was to know when the train would arrive and when it would leave. From this we got time zones and more importantly, a fascination with knowing the particulars of the world in relation to time. The big twist at the end of the book of Fogg having actually made the trip in 80 days and not 81 because he passed the International Dateline truly was a surprise to readers back in 1872. That was the world the book was written in.

Nowadays we consider the act of travel a little ho hum. We are no longer excited by the concept of trains. It’s what a middle manager rides on his way to work every morning. It’s what the college student rides when coming home for the holidays. It is not something that is special anymore or transformative or even, in a way, magical. Giant metal cylinders full of explosive liquid soaring through the air is just something we are used to. We go into one and several hours later come out of it and poof we are a continent away from where we started. Yawn. Around the World in Eighty Days is an adventure story even with so much of the focus on the mechanics of travel, because travel itself was exciting. This is something the game 80 Days gets about the era and the book. This is what it decides is most worthy of keeping in the adaptation, because it is the central reason the book was written in the first place.

In 1872, if someone mentioned they were taking a trip around the world and planned to do it in just 80 days, well you don’t have to imagine their response. The book captures it quite well at the Reform Club and with all the public betting going on at the London Stock Exchange over whether Fogg will succeed or not. Throughout the game, you can tell this or that person of your trip and they are mesmerized at the very idea. People from all walks of life and national origin wish you well on your journey. Thus, Around the World in Eighty Days was far more interested in the particulars of travel itself, because travel itself was an adventure. It shrunk the world.

Meg Jayanth, the British Indian woman who is the game’s writer, had her work cut out for her. Unlike the original novel, she couldn’t let large passages of time such as this go unfilled. The player would be sitting there waiting for a progress bar to fill without any input whatsoever. In this case, it was a friendship with a young lady, a Miss Eleanor Williamson. (But prefers to be called Noor.) We would chat and flirt. Eventually she revealed to me that she wrote a series of highly successful adventure paperbacks. Not a suitable pastime for a lady.1 This relationship is developed over a series of small scenes as the boat continues onwards. Like all story points, it will develop depending on your responses to her and later her father. He confronted me, demanding to know if I were the inspiration for the lover in these “tawdry” books he found out about. We had some fun teasing his traditional sensibilities after that.

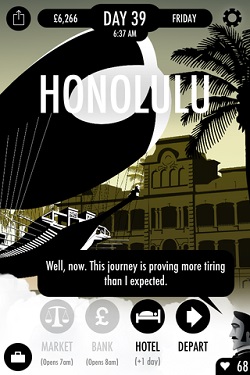

Sometimes over the journey you are given three non-story options of how to pass the time: read the newspaper, talk to the crew or tend to Monsieur Fogg. Later on in my journey, around the time when I reached Hawaii, the headline read that the girl had moved back to London to great acclaim from her fans. I couldn’t help but smile at her good fortune half a world away.

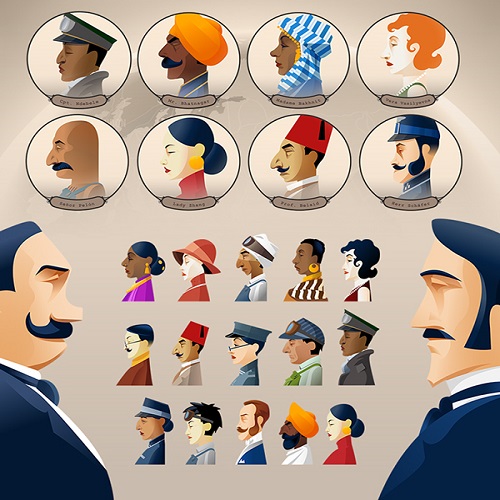

A huge difference between the book and the game is the presence of women everywhere and as conceivably anything. I mentioned earlier the airship pirate was a woman. That was not an anomaly. You will see women as mothers, inventors, travelers, scientists, actors, revolutionaries, card cheats and more I’m sure I haven’t come across yet. Women on the whole are rather absent from the novel, never mind how they are portrayed. The position of Victorian women was rather restrictive, to say nothing of non-American, non-European women. Here we see a young woman acting out against such restrictions that don’t exist anywhere else in the world.

On this trip along the book’s path, I came across the only example I’ve seen to date of our real world 1872 values seeping into our 2014 adaptation. Even when her father asks her to be more lady-like he concedes that if she can’t, couldn’t she do something respectable like enter the Artificer’s Guild (an international egalitarian organization of steampunk style inventors). This is not a utopia where sexism is dead. Women still have their place in this world, it’s just a much larger place, more fully represented and more easily pushed against. Given how our history is represented to us by the works of their time, like say a novel, one could say the game may be more accurate to real life. A novel that erases the presence of women is bound to be less accurate than one that puts them in a plethora of positions, even as fantastical as they may be.

Adapting a work to a new medium is not about transferring it faithfully, every word intact. It’s about recognizing the core of that work and transferring that. We understand, as a video game, the great departures 80 Days has to make in the name of filling all the potential space the player can cross. With the above example, we understand the need to fill the empty spaces upon the journey already traveled. We also understand the nature of the material used to fill such spaces. It cannot conform to the sensibilities of the world and its author in which the original was written, but to the sensibilities of the world and the author of today. So, what of the adventures that do happen in the book?

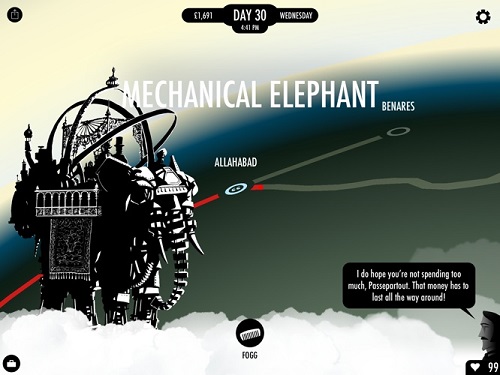

Let us move on to India. In the novel, the report that started off the entire trip was the news of the completion of the rail line from Bombay to Calcutta. It meant there was now a through line of modern travel across the globe. This turns out to be a lie as there was still quite a lot of miles of track yet to be laid. Instead, Fogg procures an elephant at great expense to get them to Allahabad to catch the other half of the rail line to Calcutta. This is also possible in 80 Days, though the elephant is mechanical and instead of buying it you are merely buying passage on it.

Along the way they came across Brahmins ready to sacrifice Aouda, a young Indian woman, wife to the now dead local rajah. She was being lead, drugged with hemp and opium, to her husband’s funeral pyre where she was to burn with his body. Fogg and company will not leave her to her fate and make a daring rescue attempt and escape.

Remember that imperial nature of the original novel I mentioned. This is probably the biggest example of it. This is the most active representation of showing the white man’s superiority as well as throwing in a damsel in distress to boot. The language in particular used to describe the situation, “a barbarous custom,” “we have no power over these savage territories, “theater of incessant murders and pillage” is not a pleasant read nowadays. The ritual in question is a suttee (or sati if you’re not a British colonialist), which is where, as Sir Francis Cromarty is so kind to inform us, a woman will become a voluntary sacrifice to burn with one’s husband on his funeral pyre. Voluntary should be in big scare quotes, as the treatment the woman would receive should she not “volunteer” is quite horrendous as well.

This seems like a good time to talk about presentation. Because other than some rather nasty word choice from the English officer accompanying Fogg and Passepartout on this leg of the trip, this seems rather reasonable. Burning a woman with no other real option is quite a barbaric act and jumping in there to pull her out of there a righteous course of action. However, something to consider: how accurate is this explanation? Furthermore, how accurate is this situation at all?

At the time most of Jules Verne’s readers would likely have little knowledge of an area even the novel admits the English have little control over or presence in. I’m thinking any reader nowadays would have even less of an idea. The only connection I myself have to this information is the book Around the World in Eighty Days.

On this point I thought it prudent to ask someone who knows more than I do. So, I asked an Indian friend and he referred me to Shivam Bhatt who gave me quite the educational crash course. The short and relevant upshot of which is, it’s complete and utter bullshit propaganda on the part of the British. And not even the logistically understandable type of propaganda where there might have an actual example to sensationalize. Bhatt was kind enough to explain, in detail, why this specific event, with the people involved, their ethnicities, their regionalism and given location is completely ludicrous.

Also, given the circumstances, after her rescue, Aouda has nowhere else to go but with Fogg and Passepartout. But that’s okay, she fell in love with the English gentleman. Which itself is okay, because (I am not making this up, the book itself gives this very reason) she was educated like a western woman and would make a fine match. Furthermore, in checking this section of the book again for the correct (or rather the published) spellings I found this description of Aouda, “The woman was young, and as fair as a European.” Didn’t notice that the first time around. I have neither the time, nor the patience to deal with everything that’s wrong with that sentence. Sufficed to say, that phrasing is used in order to mitigate outcry when Fogg eventually marries her.

Yes, ultimately the characters did the right thing. Forcibly burning a woman at the stake is wrong, regardless of culture, and should you see this happening before you I would hope that you too would stand up and stop it. However, the demands of fiction are different from the demands of the real world. Jules Verne wrote the Brahmins crossing the paths of Fogg and his group traveling through the jungle in the first place. They didn’t exist prior to being written. Everything created in a work is the prerogative of the author.

In any case, Meg Jayanth is not Jules Verne and 1872 is not 2014. This encounter did not have to be here. Much of the rest of the game is invented. My little flirtatious liaisons upon the Indian Ocean steamer were not in the book. Neither was the possibility of using the Trans-Siberian Railway, nor were airships. Yet, there is Aouda being lead in a smoky haze along by a large crowd of Indian men. I am given the option of moving on or mounting a rescue. Well, I was trying to match the book as closely as possible. Rescue it is.

I’m glad so I did, for I was captured almost immediately. The group is not a funeral party on route to a sacrifice, but a revolutionary guerrilla army against British imperialism in Northern India. Fogg and Passepartout are taken before their leader, Aouda. The whole thing was a ruse to lure soldiers in the northern jungles. Aouda herself turns out to be quite the Indian nationalist. The game plays off of the knowledge of the player. The scene of the marching party is so closely paralleled to the book and yet should you act, it rips the rug right out from under you.

Over the next few days, a relationship does develop between her and Fogg. Instead of a savior though, she sees a kindred spirit in Fogg. She is awed by his daring and his initiative to attempt the quest of traveling around the world. We are held a few days, Auoda inviting Fogg to her tent in the evenings, before she relents. Seeing us as no threat (You did decide not to make a ruckus did you not?) she escorts us the rest of the way to Calcutta. She and Fogg say their farewells and she heads back into the jungle to continue her campaign for freedom.

Like Fix, Aouda didn’t have to be included. The world in 80 Days already much grander than Verne’s novel. Completely new content would not have been amiss, just like it wasn’t in the rest of the game. However, whereas Fix was a simple nod to the original story and nothing more, Aouda was a statement. We live in a post-colonial world and with all that implies. We recognize and understand racism, sexism and imperialism even if we may not like confronting their realities. 80 Days is an adaptation of a work that is racist, sexist and imperialistic.2 These aren’t its main points or even minor ones. They are the unstated background radiation of beliefs that a European such as Verne could not help but have.

Fogg was a modern man of the time. Careful time keeping was something previously unnecessary and frankly unheard of before the train revolutionized travel and trade. Fogg is a man of habit whose runs his life by the meticulous movement of the hands of the clock. He epitomizes this new era of a fully connected, shrinking world finally coming into being. In this he can be seen as a progressive. He is the forward-thinking man, both of his travels and of society. He is kind and treats people as equals. Or as equal as a man of his station and upbringing can conceive of equality. Aouda having a western education (and apparently can pass as white) makes her suitable for a wife, she is still Indian and he still wants to marry her. He does respect her as a person. It’s not Fogg’s treatment of her that we cringe as, but Verne’s.

The book Aouda’s autonomy is still limited though. She is a victim of circumstance after circumstance. She comes under the protection of a kind wing and decides to continue on. One could question if that is a real choice. However, the romantic in me likes to think that the choice was not made due to lack of other options, only in spite of them. That she would make the same choice were she free of the threat these Brahmins posed towards her. 80 Days seems to think so as well. She falls for Fogg once again. He is not a savior and she is not a victim. This time the focus is firmly on her own interest in him. He is a man of travel and as previously mentioned this is an era where that itself is special. It’s the main reason Aouda decides to let Fogg and Passepartout go. She too is enchanted by this notion of making the trip around the world and of the man participating in this almost magical rite. With that, the question between them falls away.

The issues of racism, sexism and imperialism don’t disappear in the adaptation thanks to our more “enlightened” sensibilities. The issues still come up throughout 80 Days. They are merely reframed. Sir Francis is still spouting off his imperial propaganda, but now the world does not conform to it. Women still struggle beyond their Victorian dictated station at times, but we see the struggle and so many more doors are open. And the nations of the world, even in the more utopian fiction of 80 Days, spill their blood and cry out yearning to be free.

Possibly the greatest reframing of the whole endeavor is the sidelining of once central Phileas Fogg. In the novel he is framed as competent, kind, and detailed oriented, if a little too obsessed to the exclusion of what goes on around him. He is presented as the ideal English gentleman of the era. His eye on the prize, doing what no one else can, but will still stop to help others in dire need. In the game, he is a passport. His presentation is almost completely reversed. Fogg comes off rather incompetent, after all he made this outrageous bet without a travel plan. He is almost extraneous to the entire trip as we as Passepartout are doing all the work. Yet, everyone accepts that Fogg is the man to make such a journey, because he is an English gentleman. He is existing off of the prestige his position in life grants him, not his actual ability. One could read that as a recognition by 80 Days of the white superiority being touted by the original novel and undermining it through the stark framing of player’s own position in the world or as 80 Days standing behind Fogg — and by extension Verne — pointing at him in silent, gentle ridicule as his actual importance is laid bare to see. Yet, even in this reframing, the core of who Fogg remains. He is still determined, still kind and still a little bit obsessed. He is simply not placed upon a pedestal and becomes a little more human as a result.

80 Days is an adaptation. Adaptation does not mean being a slave to every facet of the text, but the core of that text. The core is with the fascination of travel and to be in awe at the daring exploit that trying to go around the world in 80 days means. The work has been updated for the modern day, but an adaptation would not work simply set in the modern day. We could travel around the world in under 80 hours if we wanted to. A modern adaptation meant changing the world, not the period, the book was set in. I need not have followed Fogg and Passeaprtout’s original voyage set out in the novel to realize how 80 Days captured original work’s essence. The entire game is a game of travel and the excitement of what is wild, new and different in the wide-open space of possibilities on our fair Earth. I didn’t have to, but following Fogg helped me see something else: where we are these one hundred and forty-two years later.

The problems of racism, sexism, imperialism and white privilege still exist. Their manner, execution, form and intensity have changed, but they are still ruling factors in our world. We can see these factors and how they rule us like we couldn’t all that time ago. These issues are recognized in the game as we recognized them in 2014, just as the book recognized them as one would in 1872. We are given the same characters, the same people, but look at them with different understanding. Fogg and Passepartout continue on. Aouda can no longer follow, cannot be in love. She has her own country to fight for but wishes them success in their adventure just the same.

Comments